Step into “The Black Experience in Lee County” exhibition at the FGCU’s Archives and Special Collections, and several words immediately come to mind: resilience, tenacity, inspiration, community.

“We focused on positive stories and pride,” says Bailey Rodgers, the archives coordinator. “We wanted to shine a light on how incredible the Black community is in Lee County.”

The exhibition, which is free and open to the public, is a collaboration between FGCU and the Lee County Black History Society that will remain on display through April 28 in the archives gallery, room 332 of FGCU’s Bradshaw Library. Viewing hours are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday-Friday.

When Rodgers first sat down with archives assistant Viviana Whalen to discuss future projects, the pair knew they wanted to create an exhibit on Black history in Lee County. They began considering a possible exhibition in 2019, but they hesitated to move forward with it. “We didn’t feel comfortable because it’s not our story to tell,” Rodgers says.

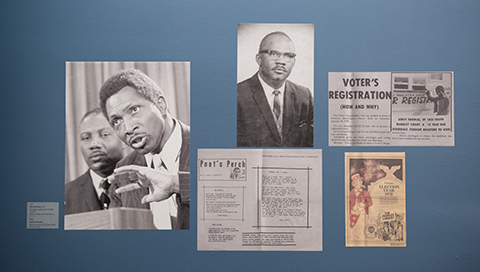

The two worked on other projects, including an exhibition on the fight to win the right to vote for Black Americans throughout the 20th century. That’s how they came to meet exactly the person they needed — Jarrett Eady, a fourth-generation native of Lee County and a former chair of the Lee County Black History Society Board of Directors. Eady agreed to serve as an advisor for the project and linked the Library Archives staff with the history society.

Much of the memorabilia, primary source documents and archival information used for the exhibition is on loan from the Lee County Black History Society’s museum, the Williams Academy. Other items are on loan from Mt. Olive, the Trinity Church, the Dunbar Community School and Audrea Anderson, a former FGCU staff member whose late husband was the county’s first Black judge.

Whalen and Rodgers remember one of their early meetings with Eady, when the pair were beginning to assemble the fragments of history for the exhibition. They wanted a piece of stained glass for one corner of the exhibit to visually highlight the role of churches, but they weren’t sure how to go about getting it. When they asked Eady, he simply nodded, pulled out his cell phone and began making calls. In less than five minutes, he’d tracked down just what they needed. Casola Stained Glass in Fort Myers was happy to loan a beautiful piece for the exhibit.

“The beauty of this exhibit is that it’s able to harness the manpower of the university and the resources of the Black History Society,” Eady says. “And it shows a level of buy-in from the community itself — people trust the university enough to donate their artifacts, knowing they’ll be on display.”

“It’s going to be a great success,” says Charles Barnes, current chairman of the Black History Society. “I’m glad to see the connection this is creating between the university and the Dunbar community.”

In curating the exhibition, the team knew they wanted to focus on pillars of the community and sacred spaces. The pillars were the early trailblazers and role models who laid a path for Black Americans to thrive in Lee County. They began with Nelson Tillis, the first Black man in Lee County, who arrived shortly after the Civil War in 1867. With his wife and children, Tillis farmed 110 acres on the north bank of the Caloosahatchee. Today, his descendants are successful members of the Fort Myers community.

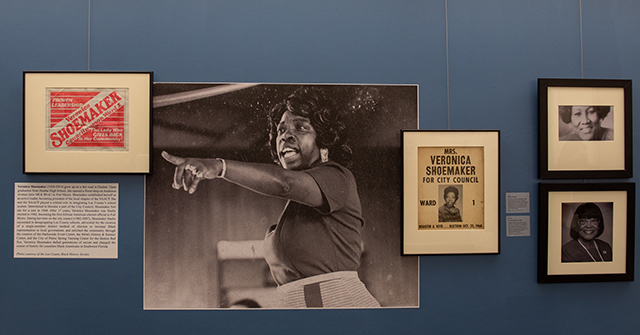

The exhibit also highlights Veronica Shoemaker, whose name many people in Lee County know because of the boulevard that bears her name in Fort Myers. But fewer may know the legacy of the prominent community activist and first Black member of the Fort Myers City Council. She ran 17 times before finally being elected in 1982. Also featured are Judge Isaac Anderson Jr., the first Black judge in Lee County, and Dr. Ann Knight, longtime city councilwoman and advocate for Black education.

For sacred spaces, the exhibit touches on the importance of churches within the Black community, especially the four earliest churches. It also includes places like McCollum Hall, once a dance hall and the social heart of the community. “You drive down Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and you see these places,” Whalen says. “They’re not just buildings. Amazing things happened there — NAACP meetings, rallies for voting rights. It’s truly incredible, the history that has happened in Lee County.”

When the Library Archives team began carefully assembling the pieces that would tell the story of the Black experience in Lee County, they chose to emphasize the themes of resilience and tenacity, foregoing the sadder parts of the narrative in favor of hope. They want visitors to leave with a better understanding of the Black experience in Lee County and also a deeper understanding of the shared human experience.

“It ultimately goes back to the resiliency of the human spirit to overcome obstacles,” Eady says. “If we’re able to see the nexus that connects us all — our common interests, outside of demographics — that’s how we bring together a just society.”