When Annemarie Connor utters the phrase “our college students with autism” in conversation, it usually elicits a look that says, “Wait – what? College students with autism?”

At the time she joined Florida Gulf Coast University’s occupational therapy faculty in 2017, she says Adaptive Services had 42 or so students who identified as having autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and requested accommodations. This school year, the number is 101.

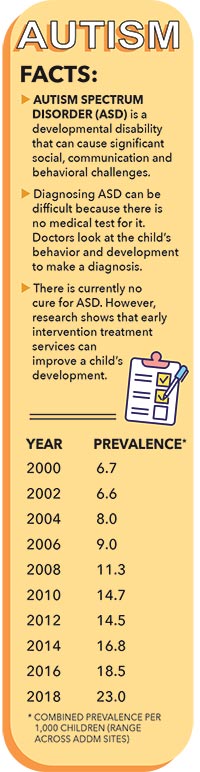

This growing campus population reflects a wider trend. Nationally, the prevalence of autism has skyrocketed from one child in 150 in 2000 to one in 44 last year, according to Centers for Disease Control & Prevention statistics.

“A good portion of why that is, is that we’re getting better at diagnosing individuals, particularly those who have autism but have average to above-average IQ,” Connor explains. “We’re understanding people’s needs better.”

But society is not keeping up with the need for more resources for families grappling with the developmental disorder, which ranges widely in severity and can be diagnosed within the first two years of a child’s life – but often isn’t until much later. Services lag far behind the mounting need in many communities, including Southwest Florida.

Filling the gap

All these factors, along with research Connor already was conducting when she arrived here, fueled creation of FGCU’s Community Autism Network a year ago. The multidisciplinary initiative aims to turn evidence-based research into educational and clinical models that can help fill the chasm in community resources — especially for those aging out of school system programs and into adulthood, the workforce and independent living. With community partners, the network also brings together practitioners and families for health and wellness events such as therapeutic playgroups and life skills training.

“FGCU has this potential to be a hub for autism,” Connor says. “We can be generating new programs, testing their validity, and in the next phase pushing them out in the community. Not only is FGCU prioritizing this, but our community is saying, ‘Yes, we want this.’”

“FGCU has this potential to be a hub for autism,” Connor says. “We can be generating new programs, testing their validity, and in the next phase pushing them out in the community. Not only is FGCU prioritizing this, but our community is saying, ‘Yes, we want this.’”

What started as a grassroots effort to involve faculty and students from strategic disciplines in her autism intervention research has gained endorsement from university leadership, institutional seed funding and the backing of community philanthropists.

Shawn Felton, interim dean for Marieb College of Health & Human Services as well as executive vice president for Academic Affairs, calls it “the right thing to do” and sees autism as another field of excellence that FGCU can develop as an institution.

“They are building something that can make an indelible impact,” Felton says of Community Autism Network. “Their motivation and work really demonstrate the spirit of FGCU from day one: You roll up your sleeves and get the job done. They recognized a huge void in Southwest Florida and have been really trying to connect all the services.”

Already, the network’s efforts through teaching, scholarship and service have yielded results:

• 250-plus hours of group interventions, including training and educational opportunities for members of the autism community, service providers, family members, faculty and students

• 18 funded FGCU student researchers and five peer-reviewed articles

• More than $1.4 million in grants and donations, including $1 million from the Golisano Foundation

• Multiple news features about programs such as Putting Along the Spectrum, which provided young adults with autism the skills to help them gain comfort and confidence on a golf course.

Connor’s and the network’s commitment to improving resources for the community inspired Theresa Lemieux to get on board as an advocate as well as a donor after participating in one of the network’s programs. The retired schoolteacher has a 21-year-old son with autism and worries how he will live independently; her daughter also has youngsters diagnosed on the spectrum, so Lemieux sees a wide range of need.

“I could see the passion Annemarie had was very much like the passion I have about how little there is in the area and how much the community needs to be aware that more providers and services need to come to this area,” Lemieux says. “No one is prepared. It’s thrown everyone for a loop.”

The path to becoming a hub

The Community Autism Network is relatively new at FGCU, but the university is not new to the field of autism syndrome disorder. This spring, FGCU’s Promising Pathways autism conference celebrated its 15th anniversary, drawing a crowd to hear returning keynote speaker Temple Grandin, likely the most well-known and most influential individual in the autism community.

The annual gathering is held in April, which has been earmarked as a month to raise autism awareness since the 1970s. Despite five decades of educational efforts, the public still struggles to understand autism and the vast need for more resources and research. Autism is a developmental disability that can cause significant social and communication challenges as well as behavioral issues such as repetitive activities or resistance to changes in routine. The learning, thinking and problem-solving abilities of people on the spectrum can range from gifted to severely challenged, according to the CDC’s description.

Connor’s research and the Community Autism Network’s mission focus on higher-functioning adolescents and young adults, an underserved group within an underserved population. Less than a third of individuals with ASD have intellectual disabilities, and 69% have average or above-average IQs. Yet they can founder without the resources of school-system programs and clinical services as they transition to adulthood.

“We’re looking for ways to help individuals who have great potential to engage in independent living and careers but are struggling because of the social challenges of autism,” she says. “Only 39% of individuals with autism who go to college graduate, and it’s because of social aspects and mental health issues related to that.”

Connor describes it as a cycle: Social anxiety prevents students with autism from engaging in the classroom and in campus life; the isolation spurs depression; depression lowers motivation to learn and often leads to dropping out. Mental and physical health have long been accepted as critical to overall student success — even when autism is not a factor.

To help break that cycle, the Community Autism Network has developed initiatives like Assistive Soft Skills and Employment Training (ASSET). The 13-session program focuses on communication, critical thinking, networking and psychological wellness among other skills.

“Our data consistently shows improvement in social confidence and functioning and confidence in applying those skills in work-based settings,” says Connor of ASSET’s results.

“Our data consistently shows improvement in social confidence and functioning and confidence in applying those skills in work-based settings,” says Connor of ASSET’s results.

Success is partly due to a multi-disciplinary approach that brings together faculty and students in social work, occupational therapy, education, psychology, counseling and rehabilitation science. That’s a critical lesson for FGCU’s practitioners-in-training, who already are using the ASSET manual to help service providers off-campus implement the program.

“Autism is complex, people are complex, human behavior is complex and there is such variety with ASD diagnosis,” Connor explains. “More often than not, for the best services to occur you need to be interfacing with colleagues from other disciplines. That results in the best care, and that’s what we’re modeling here.”

Creating Club CAN

Alice Norwood, a junior social work major with autism, completed ASSET and another Community Autism Network program that delves into getting and keeping a job. She describes her autism, diagnosed in 2020 when she was 18, as mostly a social impairment. Sometimes, she finds it difficult to set boundaries with others and to recognize them in others, she says.

“I struggle to communicate effectively and appropriately sometimes,” Norwood says. “I struggle with fitting in, but I have actually found a lot of confidence. I’ve told my closest friends that I’m on the spectrum, and it doesn’t faze them at all.”

Norwood made such an impression on the network team that she was invited to join as an undergraduate researcher and help graduate students run the programs. She’s also helping them develop Club CAN, a drop-in autism-friendly space on campus where students can socialize, study or exercise.

“This has been an amazing opportunity, and I am so grateful for it,” says Norwood, who plans to pursue a master’s in social work.

“Alice is the best advocate on the team on any topic related to autism – even among people who are highly educated on the topic,” says Kevin Loch, who’s working with the network as part of his master’s in occupational therapy program. The network is helping him and others in the next generation of practitioners to develop skills and tools through hands-on experience that complements classroom knowledge and spans disciplines, he says.

Having close relatives on the autism spectrum is part of what inspired him to seek experience working with young adults transitioning into independent living.

“I saw the whole development of their lives and the things they struggled with,” Loch says. “I came in knowing I wanted to gain experience with this population. Going out into the community and interacting with families and hearing their struggles fueled that fire. I wanted to go out and make a change. I’ve already been doing that thanks to the Community Autism Network.”