In the final days of World War II, the Swedish Red Cross White Bus Rescue Mission was a joint venture between the Swedish Red Cross and the Danish government to rescue thousands of inmates from Nazi concentration camps. The Ravensbrück concentration camp in northern Germany held 130,000 female prisoners from 1939 to 1945. Only 15,000 survived until liberation, many of those rescued by the White Buses and brought to Malmö, Sweden.

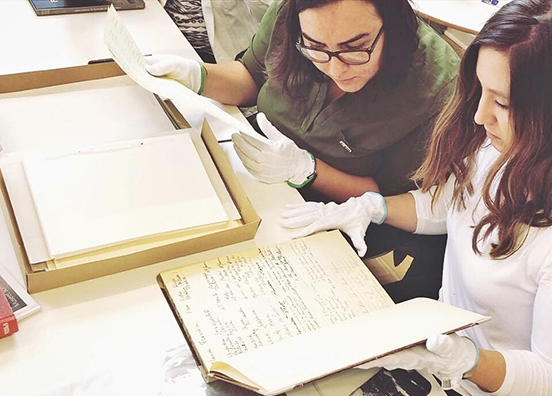

The former concentration camp at Ravensbrück is now a memorial site that VandeBurgt, head of Archives, Special Collections, & Digital Initiatives at FGCU, and her student archivists visited this past October. They also traveled to Malmö and Lund, Sweden, to meet and work with curators and museum educators on a new exhibit about the Ravensbrück survivors and the White Bus Rescue Mission, which opened Jan. 6 at the FGCU Library Archives and is on display until May 2.

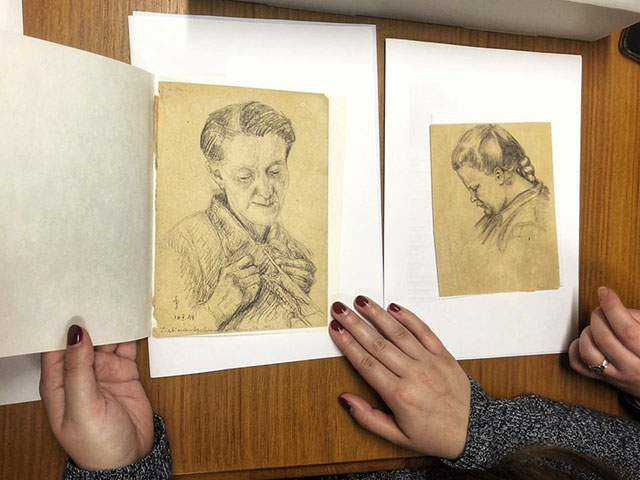

Twenty-five items are on loan from Malmö Museum and the Lund University Library Archives for the spring 2020 exhibition, “To Life: The Liberation of Ravensbrück,” which commemorates the 75th anniversary of the 1945 liberation of the concentration camps.

The five student archivists who accompanied VandeBurgt on the European trip are Bailey Rodgers, Jordan Curtis, Kinsey Brown, Abby Winslow and Adrian Sanchez. Rodgers is an archives specialist I and the other students are archival assistants in Library Archives.

“We were planning ‘To Life’ this past summer,” Curtis said, discussing the lengthy organizational process for an exhibition of this scale. Originally from Buffalo, N.Y., Curtis graduated in December with a history degree.

When the excursion was first conceived, not all five students were going to make the trip because of limited funding.

“And we were each handed an itinerary for Germany and Sweden,” said Winslow, a Knoxville, Tenn., native who is the first in her family to attend college and in her second year as a graduate student in public history. “We were surprised!”

“We were all going!” Curtis added.

VandeBurgt, Curtis and Winslow often finished each other’s thoughts and sentences when talking about the trip. They explained that the Seidler Fund and the College of Arts & Sciences had made a generous grant that allowed all five students to accompany VandeBurgt to Ravensbrück and the museums and archives in Sweden.

As part of the project, VandeBurgt asked each student to research one Ravensbrück survivor, to narrow down an event as vast as the Holocaust to something on which they as historians and curators could focus.

“History is often reduced to numbers and dates,” VandeBurgt said. “I didn’t want that for them. I asked them all to study and research one survivor so that would become personal for them.”

A moving experience

There were moments on the trip when VandeBurgt felt she had done the wrong thing by making the Holocaust so deeply personal for the students.

‘“What did I do?”’ VandeBurgt asked herself on the train to Ravensbrück. “I could see it hitting them, and I had a moment where I thought, ‘I might have made this too personal. I don’t want to do any harm.’”

“I didn’t know you were worried about that,” Curtis said, shaking her head. “That didn’t ever come across, to any of us. As history students, we learned about the Holocaust, and I was surprised at how much we didn’t know until we learned about the people.”

“I don’t think we could have told these stories without being in their footsteps,” Winslow added.

“You didn’t hurt us,” Curtis reassured VandeBurgt. “It meant more, knowing.”

“We want to ensure in the show, too, that nothing we do could possibly do harm to anyone,” VandeBurgt said. Considering this interview itself was very emotional, it is doubtful the tears shed during this conversation will be the last involving the “To Life” exhibit.

The students learned that in addition to performing strenuous manual labor, the female prisoners at Ravensbrück had bones removed from their lower legs, muscles and nerves transplanted, and bacteria introduced during Nazi experiments to research the treatment of post-battle complications such as gangrene. VandeBurgt is particularly galled that the guards and medical doctors experimenting on women at Ravensbrück were also all female, but said she was intrigued by the strength and grit of the “rabbits,” so-called because of how they hopped around on wounded, infected legs.

The women rescued by the White Buses in the spring of 1945 stayed in Malmö Museum when they disembarked from the ferries. Late one night on their 2019 trip, VandeBurgt and the students took the same ferry crossing and walked to the same museum where many of the survivors were cared for after arriving in Malmö.

“We started on ferries, just like they did with their buses,” Curtis said. The White Buses were loaded onto ferries to make the crossing from Denmark to Sweden.

“It was really emotional,” Curtis added.

The people part of history

Memory is a large part of the exhibit, and the FGCU group’s own memories of the trip are no different. And not all are traumatic. Every name they mentioned elicited a laugh, a smile, a heartfelt sigh. The names of the people helping them tell the story of Ravensbrück include Kathleen, Karin, Samuel, Richard, Tomas, Ulrika, Anders, Tobias, Häkan, Magnus, Bo, Margaret … .

“Everyone opened their doors to us, everyone spent hours and hours and hours with us,” VandeBurgt said, referring to people they met in Germany and Sweden.

Identity is the other vital part of the exhibit, and VandeBurgt is committed to returning names to women who were once only numbers and symbols.

“A big part was identity, and we wanted to give that back,” Curtis said.

The names of women in the exhibit are shorthand for people with whom they are all intimately familiar: Wanda, Edith (“The little girl!” someone exclaimed), Bernard and Anita, Judith, Nadine, Trien and Elsie.

What VandeBurgt and her students have learned is immeasurable — stories to last a lifetime, a lifetime in each story they learn.

“This will be the first time this story is being told in the United States,” VandeBurgt said.

“We’re very honored,” Curtis added.

Telling a special story

The exhibition will flow from the Holocaust to freedom, with small groups of exhibit-goers led by a student archivist who will share stories about each featured woman.

“The challenge is, ‘How do you tell a story visually?” VandeBurgt asked.

“I love history. I have a definite passion for it,” Curtis said, continuing VandeBurgt’s thought. “But for those who aren’t passionate, we have to find a way to share history and the memory of events.”

“It was hard going, but we were together,” Winslow said of the emotional trip. “Being there, you could feel it. Walking through there – it brought it to life.”

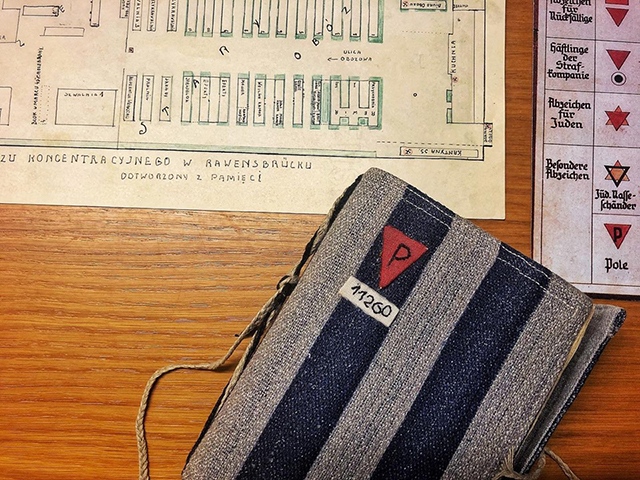

Concentration camp prisoners were reduced to numbers tattooed on their arms and symbols sewn on their clothing. A poster hung in the administration building at Ravensbrück denotes, in German, the meanings behind the cloth symbols prisoners were forced to wear to identify them as Jews, political prisoners, or belonging to other groups.

In explaining why that poster will be the singular Nazi-era piece in the exhibit — with no other reference to Nazis — VandeBurgt said, “We refuse to give them that,” meaning exposure or publicity.

The Swedish Red Cross arrived at Ravensbrück on April 24, 1945. Years later, the former prisoners were shown a documentary titled “Every Face Has a Name” by the Swedish filmmaker Magnus Gertten, which documented their arrival in Malmö by ferry. The liberated prisoners were able to identify their friends, but their own faces and bodies had changed so much during their time in the camps they were unable to recognize themselves. The “freedom” side of the exhibit will feature five still shots from the documentary and use corresponding materials from Malmö Museum and the Lund University Archives to bring the women to life.

“This is really going to impact our students,” Winslow said.

In addition to the 25 items from Sweden, three items will be on loan from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. These items belonged to Elsie Ragusin, an American who survived Ravensbrück and plans to attend the Feb. 4 opening reception of the “To Life” exhibit. The New York native, now 98 and living in Florida, was visiting her grandparents in Italy when she was arrested and taken first to Auschwitz, then Ravensbrück.

VandeBurgt smiles as she tells the story of how Ragusin rebelled against her captors and sewed “USA” in defiance on the red triangle she was forced to wear at Ravensbrück. It was yet another example of how these women took back their identity when the Nazis tried desperately to inhumanely reduce them to numbers and symbols.

In fact, VandeBurgt and her students planned to make one more exhibit-related trip before the exhibit opening: the Edgewater home of Elsie Ragusin.

“We’ve been invited for tea,” VandeBurgt beamed.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

About the exhibit

What: “To Life: The Liberation of Ravensbrück”

When: Through May 2; opening reception 5:30-7:30 p.m. Feb. 4

Where: Wilson G. Bradshaw Library, Archives & Special Collections, Room 322

Watch video:

[/vc_column_text]