Much like the 400 dolphins she spends her summers with, water is the ideal place to be for Allison Sanchez.

As a research assistant with the internationally renowned Wild Dolphin Project, Sanchez (’25, integrated studies) helps document communication, behavior and social structures in wild Atlantic spotted dolphins. What began as a childhood love of the beach has deepened into a passionate pursuit of graduate studies in environmental science and an internship that has evolved into a career-defining experience.

“That kid with the bucket of critters”

Growing up in the Jupiter area of Florida’s southeastern coast, Sanchez frequented local natural treasures like DuBois Park and John D. MacArthur Beach State Park. She loved being outdoors — toes in the sand, hands in tide pools, eyes scanning the shoreline for living, moving creatures.

“I was always that kid with the bucket of critters, collecting things and doing experiments,” Sanchez says.

Starting in third grade, she attended a marine biology summer camp at MacArthur Beach, eventually becoming a junior camp counselor. But when it came time to look at colleges, Sanchez wasn’t sure what she wanted to study.

“It was my mom who said, ‘You light up when you talk about the environment. You can’t do anything else. It’s your thing.’”

Enticed by FGCU’s Water School vision

Sanchez was drawn to FGCU because of The Water School — even before its home in Academic Building 9 existed. The university’s plans signaled a long-term commitment to environmental problem-solving, and she enrolled based on that vision.

“I really liked the concept of The Water School. It was not a building yet, but it was a promised building and I’m here because of that promise.”

“Allison’s decision to attend FGCU based on the promise of The Water School reflects how FGCU’s commitment to applied water and environmental science creates a clear, continuous pathway from student interest to graduate training and participation in internationally recognized research,” says Rachel Rotz, the program coordinator and an associate professor of marine and earth sciences at FGCU.

As a student researcher, Sanchez works with Barry Rosen, ecology and environmental studies professor in The Water School, investigating harmful algal blooms by analyzing samples from Lake Okeechobee and the Indian River Lagoon. Sanchez also holds five different scuba certifications, including one for scientific diving, which she earned at FGCU.

“Scuba diving really influenced my look on conservation,” she says. “I was able to be underwater, which is my favorite place, for longer periods of time. You get to see the ocean in a different way and how a coral reef works — this network of lives, like an apartment complex or a city. There’s so much going on and you get to be a part of that.”

Decoding dolphin communication and behavior

Those skills now travel with Sanchez far beyond Southwest Florida and into one of the longest-running marine research projects in the world.

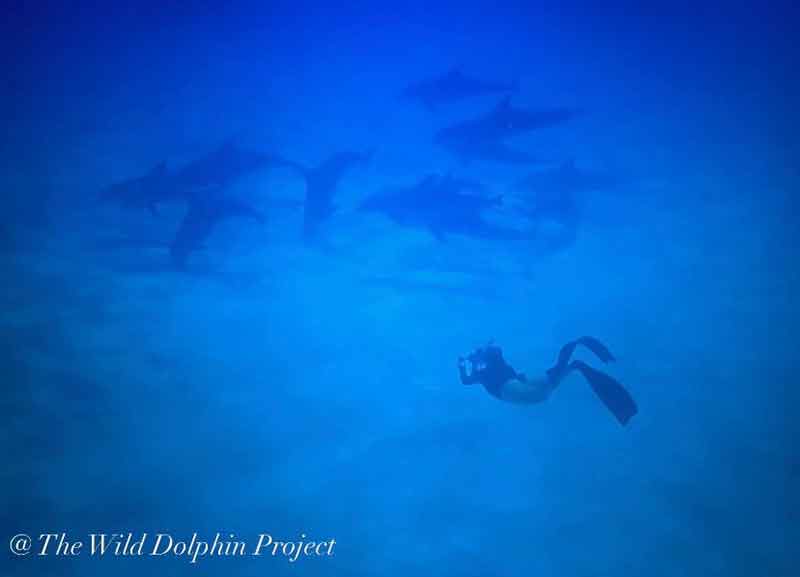

The Wild Dolphin Project has been studying the same pod of Atlantic spotted dolphins in the Bahamas since 1985. The research team has been tracking individuals across generations to study life history, genetics, habitat use and social behavior. Using underwater audio and video recordings, they’re also working to decode dolphin communication and explore the potential for two-way interaction between humans and dolphins.

Sanchez started interning there in 2021. Now, as a research assistant, she and other team members practice a trust-based, non-invasive research model. Rather than capturing or tagging animals, they enter the water on the dolphins’ terms, observing natural behaviors and allowing the animals to choose whether to engage.

“We’re in their house,” Sanchez says of the 400-plus dolphins in the pod.

“At first, I thought ‘I’m never going to be able to tell them apart.’ But they have such big personalities. Their spot patterns are all different, like our thumbprints. They’re all completely different.”

Sanchez names a few: Moose. Nautica. Pointless. Kansas has a super raspy, Janice Joplin-like whistle, she says. Does she have a favorite?

“Sycamore is the prettiest girl I ever saw,” Sanchez says, describing the dolphin as “chill,” “the most curious” and “an old soul.”

Sycamore’s behavior also suggests this female plays a role as a peacemaker, according to Sanchez. Sometimes dolphin play-fights turn aggressive, and they’ll slap each other with their tails. The researchers study the dolphins’ body language during such episodes.

Sanchez has witnessed Sycamore appearing to try to intervene between fighting pod members.

“She’ll rip sea grass up from the ground or a piece of sargassum and try to entice them to play. And when they don’t want to play, she tries to get us to play. And we’re, like, ‘Sycamore, we’re working. We can’t really be playing with you right now.’ She’s just the sweetest.”

You might also be interested in this story:

Meet the Eagles protecting sea turtle nests in Southwest Florida

On board the Stenella

The team travels on a catamaran called Stenella between Florida and the Bahamas. A typical day starts as early as 5:30 a.m. with breakfast and equipment checks. When dolphins appear, the pace shifts to what Sanchez calls a “firefighter” kind of readiness — it’s all hands on deck. The team moves quickly to enter the water, document individual dolphins, review identification from previous encounters and log observational data.

Sanchez describes one of her most unforgettable encounters from her first trip with the project, when the team spotted dolphins in a tide line filled with trash. Instead of focusing on data collection, the researchers entered the water to remove what they could, repeatedly filling their unzipped wetsuits with debris and emptying it into garbage cans on the boat.

As the humans worked to clean the floating trash, the dolphins began bringing larger pieces that had already sunk, including milk jugs, cardboard, plastic and metal — even diving with their calves in tow.

“It was like they were saying, ‘Oh good, you’re here for your stuff,’” Sanchez says. “It never gets old. It’s never the same encounter twice.”

You might also be interested in this story:

Can plants save our beaches? Students team with faculty to dig for answers

“At FGCU, preparing students to be future-ready leaders means actively supporting students like Allison. We seek out curious, motivated students who feel a genuine connection to the environment and sustainability, and we give them the support, mentorship and flexibility to dig into complex problems, contribute meaningfully and make a real difference beyond the classroom,” says Rotz.

Sanchez says she’s grateful to receive academic credit for her fieldwork in the Bahamas as well as her scientific diving certification and faculty mentorship — all part of FGCU’s culture of experiential learning. Looking ahead, she hopes to lead her own conservation initiative rooted in the RSEA framework: research, sustainability, education and advocacy.

The kid who once combed Florida’s shorelines toting buckets of critters now swims respectfully alongside wild dolphins, collecting data that can reshape how humans understand marine communication.