Facts are just that. History is full of events that truly happened and not a matter of debate. Knowing those facts is necessary for their interpretation. But what if the facts just aren’t known?

What if, for reasons specific to Florida, to Southwest Florida and even to Fort Myers, the struggles of one group of people to vote – Black people – aren’t known? Have population growth, historically segregated neighborhoods, seasonal residency and other factors left the records about local Black citizens and voting on closed pages of history?

Certainly, say several people involved in the WGCU Public Media documentary “With a Made-Up Mind: The History of the Black Vote in Southwest Florida.” The film debuts at 8 p.m. Thursday, May 18 on WGCU and will be streamed at wgcu.org.

People interviewed in the film not only know and relay the obstacles Black citizens faced to exercise their right to vote. They lived them.

Jarrett Eady, a fourth-generation Fort Myers native and the School District of Lee County’s diversity and inclusion director for 16 years, produced a 17-minute version of “With a Made-Up Mind” that was expanded into this 26-minute film for broadcast and streaming. Amy Shumaker, WGCU’s associate general manager for content, served as project director.

The effort was funded in part by a grant from Florida Humanities, a nonprofit that preserves, promotes and shares Florida’s history and culture.

You might also be interested in this story:

Archives & Special Collections a Rich Research Resource

“Made-Up Mind” takes viewers on a bumpy journey of steps forward and back, from Reconstruction to Jim Crow, from the White primary system in some Southern states that disenfranchised Black voters to women’s suffrage – a movement in which Black women played a large part. More modern electoral changes like districting in the Fort Myers City Council elections are also addressed.

Strides were made, then often lost.

Between 1944 and 1950, a local Progressive Voters League registered 116,000 Black voters, or a third of eligible Black voters in the state. The white primary was declared unconstitutional and a Congressional investigation into voter suppression was launched.

Finally, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed, breaking down state and local barriers that prevented Blacks from exercising their right to vote under the 15th Amendment, which had been passed nearly 100 years earlier.

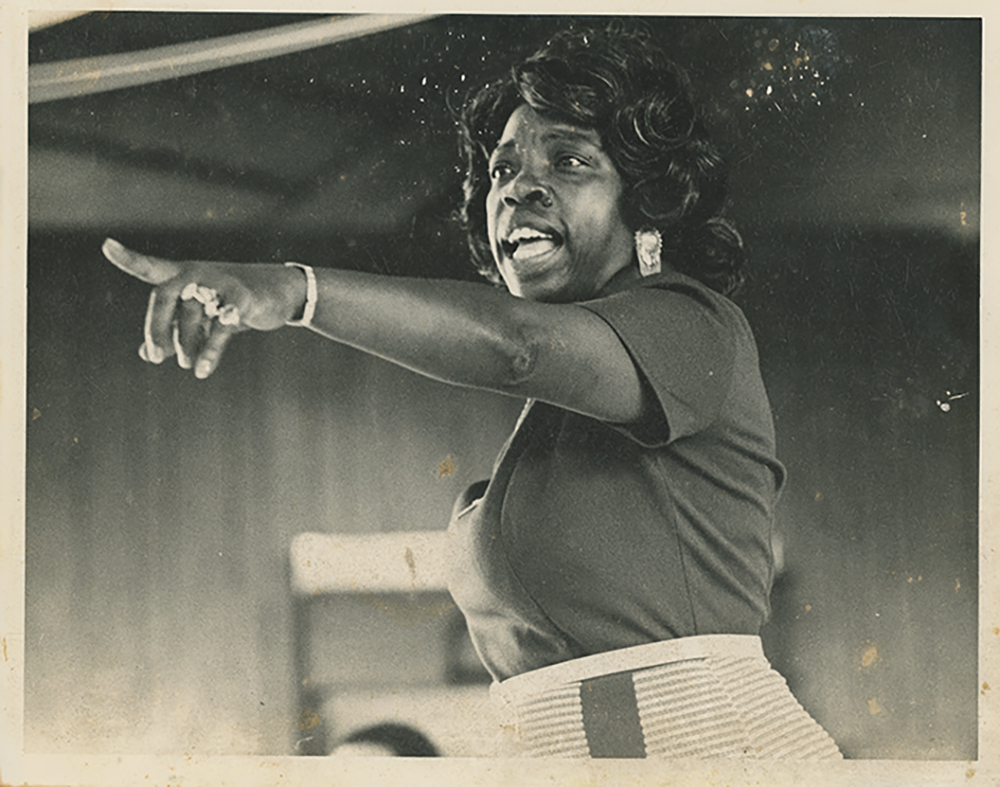

Like many others in the film, community activist Gerri Ware lived this national and local history. In it, she talks about voting for the first time – in Fort Myers – and knocking on doors encouraging people to vote. “I remember being very, very happy to have this paper in my hand,” she says, referring to her voter registration card. “I had accomplished something for the fight and the struggle.”

Voting rights were slow to be assured in Southwest Florida, which also meant it was a while before local citizens saw a Black person elected to any office in Lee County. Horace Smith was elected to the Lee Memorial Hospital Board in 1980.

The late Veronica Shoemaker, local business owner and onetime NAACP president, ran for public offices for 14 years before finally being elected to the Fort Myers City Council in 1982. Shoemaker was the last member elected at-large to the council, in a system that made citizens from all over the city eligible to hold a seat, rather than representation coming from areas or neighborhoods. She led the effort to change the way citizens are represented – by district, rather than at-large – by suing the city.

“I think most people would believe that African Americans were only denied the vote in Deep South places like Mississippi and Alabama rather than the Sunshine State,” says Jonathan Harrison, a visiting instructor at FGCU and doctor of sociology, who served as a scholar for the film. “They don’t associate Florida with the racist past of other states. In reality, Southwest Florida had a lynching in 1924, which I have studied; the Ku Klux Klan marched through Fort Myers; and African Americans were excluded from the vote by the poll tax, white primaries and the disfranchisement of felons.”

Times have changed the voters, too. “When I moved to Fort Myers from South Carolina in 1976, the elected officials including the governor of the state were Democrats. Today it’s very different,” says Audrea Anderson, a former associate vice president at FGCU. “Very few Democrats hold elected office in Southwest Florida.”

And why the title “Made-Up Mind”? It harkens to a song by the Clark Sisters gospel group: “My Mind Is Made Up.” To those in the film, a made-up mind meant action.

“Change is not going to occur by waiting on it to occur. You have to get up and do something,” Lodovic Kimble, Lee County NAACP president in the mid-’80s, says in the film.

“If you have the right to vote, you are an equal citizen in the United States,” says Martha Bireda, a writer and consultant on racial issues and executive director of the Blanchard House Museum of African American History and Culture in Punta Gorda. “The progress that African Americans have made in this country has had to do with voting.”