An avid hiker raised from a young age with a love of the outdoors, FGCU graduate Jessica DeYoung (’18, Environmental Studies) always knew she wanted to work in nature. But it wasn’t until a chance discovery in college that she learned how much she was missing when gazing at the world around her.

On a family vacation that included stops at state parks and preserves, DeYoung tried on a family member’s glasses and realized that, unlike her, others could easily distinguish individual plant leaves. She hadn’t realized how much her nearsightedness had worsened over time.

DeYoung’s discovery did more than sharpen her focus on the world around her: It has helped make her a vital asset in preserving that world for us all.

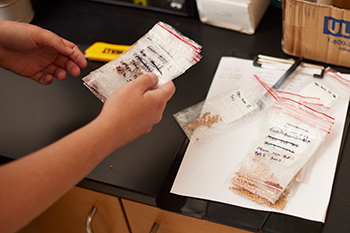

A plant conservationist at the Naples Botanical Garden, the Florida native from Charlotte County has spent the past three years gathering, storing and diligently growing seeds from plants indigenous to southern Florida and subtropical locales in the Caribbean.

She has been so successful establishing a seed bank containing the region’s many plant species – threatened, endangered or completely overlooked all the same – that she rapidly has gone from intern to a manager needing her own assistant for help with volumes of testing, data entry and cultivation protocols.

“Her passion, her knowledge, her skills matched exactly what we were looking for,” said Chad Washburn, garden vice president of conservation, of DeYoung’s role developing a program in which he was the only member when she joined the staff in 2018. “She put us way ahead of where we would have been, bringing someone on and training them.”

Hurricane Irma in 2017 helped spark conservation efforts in greater earnest at the garden, which opened in 2009 on 170 acres on Bayshore Drive in East Naples and has been a key partner to FGCU in multiple arenas.

Damage from the storm exposed well-known ecosystem threats from habitat loss, climate-related stress and disease. It further revealed the urgent need for preservation, cultivation and restoration practices.

It’s become imperative,” Washburn said of the conservation program, which now has six staffers. “We really need plant diversity to make our ecosystems more resilient. But we also need material for restoration, and she’s able to start making that happen immediately. We can’t thrive without it.”

South Florida, one of the most biologically diverse regions in North America, already has seen some 8 percent of its more than 1,400 native plants species go extinct, according to the garden, citing data from The Institute for Regional Conservation.

Only 10 percent to 15 percent of “scrub” habitat – sandy, high and dry areas favored by developers and often overlooked for preservation – remains statewide, according to garden experts, citing the World Wildlife Organization. And about half of the species living in scrub areas don’t exist elsewhere.

“We need those ecosystems,” Washburn said. “They’re incredibly diverse. Some of the stuff out there is incredibly rare. Jessica is really unlocking the secrets of how to grow some of these plants. Many have never been grown in an agricultural or horticultural setting.”

Indeed, many of the seeds being stored – frozen – and studied by DeYoung over months-long periods are prioritized in part because few or even no other botanical gardens have banked them. That’s not enough to ensure the survival of species with often unknown or untapped potential, whether as landscape plants, key animal food stocks or even potential sources of medicines.

DeYoung experiments with moisture, temperature, light, scarring, fermentation that mimics animal digestion and other factors to unearth natural and even optimal germination rates. Some seeds take more than 200 days to sprout, making for many protracted outcomes, some of the results of which she is close to beginning to publish for the benefit of other researchers, nursery managers, plants lovers and others.

Though DeYoung concedes the work can be tedious at times, there’s no shortage of field, lab, data entry and reporting work to be done when it comes to ground as uncharted as it is important.

“I love this job,” said DeYoung, excited to see the continued growth of FGCU’s formal and informal botanical coursework and surrounding activities within the environmental studies curriculum.

“I don’t go to work and think, ‘Oh man. I have to work today.’ I think, ‘I really need to work on this project so we can get these plants to grow for this ecosystem.’

“It’s such a spiraling effect. One thing always helps another. We as people are getting this benefit. But the environment, the animals, the bugs – all of that – also are benefiting from what we’re doing.”