May 1921

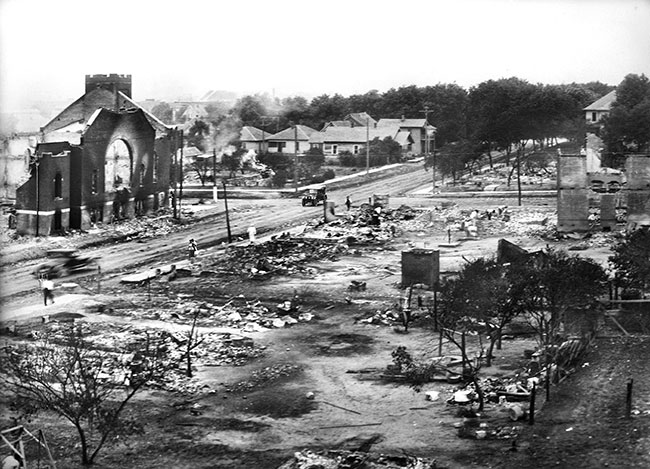

What is considered the worst incident of racial violence in America’s history took place almost a century ago in Tulsa, Oklahoma when an angry white mob descended on the vibrant Black district of Greenwood, destroying more than 1,000 businesses and homes, killing between 50 and 300 people and committing untold atrocities on the residents.

The rampage was sparked by a rumor that a Black teen had assaulted a white elevator operator in a downtown building. The Oklahoma Historical Society reports that he more likely stepped on her foot, causing her to scream. Nonetheless, the rumor raced through town and the massacre ensued. Eighteen hours later, the city was under martial law and the state’s second-largest Black community had burned to the ground.

While the massacre remained a taboo subject for decades, a state commission formed in 1997 investigated the event. Scientists and historians uncovered evidence that unidentified victims were buried in unmarked graves.

October 2020

After a first attempt in July failed to turn up any bodies, a forensic team unearthed 11 coffins in a mass grave in Tulsa’s Oaklawn Cemetery in October.

They are believed to be victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, although it will take time and painstaking work to identify the remains found there.

Heather Walsh-Haney, Florida Gulf Coast University associate professor, chair of the Justice Studies department and an in-demand forensic anthropologist, is among the experts working to uncover the truth about who was buried in this unmarked grave. With her was graduate student Sonya Concepcion Jones. They were invited to take part by Phoebe Stubblefield, University of Florida forensic anthropologist and leader of the physical evidence investigation.

For Concepcion Jones, taking part in locating the grave validated the journey that brought her to FGCU’s Justice Studies program.

Over 10 days last fall, the graduate student assisted a team of scientists investigating whether multiple victims were buried in the unmarked grave a century ago.

The work yielded evidence of 10 individual burials in one location and another nearby. The outlines of coffins, at depths of 13 to 14 feet, were found using ground-penetrating radar. The excavations unearthed wood, nails and handles from coffins, as well as biological material such as bone, teeth and skull fragments.

Concepcion Jones didn’t hesitate when Walsh-Haney asked her to take part in the project.

“As soon as she asked me, I said, ‘Yes, whatever I need to do, I’ll fit it into my schedule, I’ll rearrange things, I am down to go on this journey,’” Concepcion Jones said recently, excitement still evident in her voice.

A native of Queens, New York, she earned a BS in applied forensic sciences, with a concentration in forensic anthropology, from Mercyhurst University in Erie, Pennsylvannia, before coming to FGCU. She expects to receive her master’s degree in 2022.

“I felt this opportunity was one of my main purposes for coming to this program,” Concepcion Jones said. “After completion, I felt at peace. I felt happy with my journey in Florida, with my journey educationally, all the way from Mercyhurst to now. I felt going to Tulsa was definitely the reason I stuck with it and kept choosing forensic anthropology over and over again.”

The work being done now is the result of the state commission formed in 1997 that is attempting to determine what happened to all of the victims, identify them and ensure that their story is now told as it has been largely absent from history books for the past century.

Concepcion Jones assisted Walsh-Haney at the dig site, supplying tools and other equipment, providing an extra pair of hands and helping in whatever way she could.

Walsh-Haney’s role involved assisting with the identification and logging of osseous (bony) material and taking meticulous notes on where evidence was found, soil changes during the dig that suggested the presence of caskets or osseous material, and other significant findings. She also worked with the physical evidence team to determine where the strongest ground-penetrating radar signals were.

Large earth movers skimmed off layers of compacted soil in search of artifacts or changes in coloration. When they came upon something, the team would gently dig and graduate students would sift soil to turn up evidence.

“The process used was very similar to what I have done on scenes where we’re trying to find a clandestine grave that might contain one person, or two or three,” Walsh-Haney said. “The process was similar in that ground-penetrating radar was used to find a location where there was a subsurface disturbance or anomaly that wasn’t mirrored by what was on the surface, meaning that there were no headstones or outward signs of a burial.

“What was so unusual was the caskets were not laid out neatly, as you would expect. They were overlaying one another and put in at odd angles, as you would do hastily to hide a mass burial in a very deep trench.” Great reverence, befitting the solemn nature of the work, was shown throughout the project, she said.

“Every day we began with a prayer and every day, we ended with a prayer,” Walsh-Haney said. “All the remains, the entire time we were there, whether it was a small casket nail or a tiny piece of skeletal material, we were constantly aware of the importance of the site.”

Concepcion Jones said that as an Afro-Latina (Black and Puerto Rican), the experience was especially meaningful. She also took note of what her presence symbolized to the people of color who visited the dig site.

“I could feel all the eyes that were on me, that people were noticing that I was there and that’s the point of things like this,” Concepcion Jones said. “We always talk about how being there and showing that people of color can do everything is important. Once you see that one person, it makes you think, ‘I can do that.’ I hope that seeing me makes people feel more comfortable with the work that was being done there.”

Walsh-Haney views amplifying diversity, equity and inclusion as part of her role as an FGCU faculty member.

“I’ve spent my career trying to open up science and forensics to underrepresented minorities,” she said. “Working with Phoebe (Stubblefield) and her team has given me the opportunity to allow students like Sonya to have a real impact and to gain power back in a safe place where they can see communities watching these young, Black females use science for social justice. I’m moved and floored to even have a tiny part in this huge project.”

This site is important because it documents the systemic racism in the United States and the way that bureaucratic structures have hidden evidence of racism.”

– Heather Walsh-Haney, forensic anthropologist

Stubblefield has been part of the effort to locate the mass graves and identify victims since 1990. She was invited to join by Scott Ellsworth, a professor of history at the University of Michigan and author of the first book addressing the tragedy, 1982’s “Death of a Promised Land.” Ellsworth served as a historical consultant to the Race Massacre Commission.

She, in turn, asked Walsh-Haney to take part in the cemetery dig. The women have been friends and colleagues since they were students at the University of Florida, where Walsh-Haney obtained her bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees.

“Heather and I are sisters from different parents,” said Stubblefield, whose parents were born and raised in Tulsa. “She was the first one I thought of inviting because I trust her and I knew she would do her best to represent both me and her alma mater, UF, and to honor the victims, because I have concerns about how these individuals are described and handled as we uncover them. I instantly knew that Heather would be right there, having a decedent-focused approach to this investigation.”

Concepcion Jones said finding evidence of a mass grave “felt like a big win” because of the hard work involved and the support it offers for what had previously been unsubstantiated.

Work is slated to continue this summer and Walsh-Haney intends to take two grad students with her.

For Walsh-Haney, the Tulsa Race Massacre project has taken on additional importance, given the issues related to Black lives that arose in 2020.

“This site is important because it documents the systemic racism in the United States and the way that bureaucratic structures have hidden evidence of racism,” she said. “This massacre was not included in our history books for our children to read, for communities to know about. That’s why this documentation is so important.

“I think some people don’t understand the depth of racism in the United States, how widespread it is, how insidious it is and that there was a rich, lively, wonderful community that was wiped out by white racism. That our country hasn’t talked about it until recently is stunning. I’m proud to be part of a committee that is shining a bright light on historic racism so we can learn from it and move forward.

![]() [/vc_column_text][vc_gallery type=”nivo” interval=”3″ images=”28101,28100,28099,28098,28097,28096,28095,28094,28093,28092,28091,28090,28089,28088″ img_size=”large”]

[/vc_column_text][vc_gallery type=”nivo” interval=”3″ images=”28101,28100,28099,28098,28097,28096,28095,28094,28093,28092,28091,28090,28089,28088″ img_size=”large”]