“A plague on both your houses!” the dying Mercutio famously shouts at rival families in “Romeo and Juliet,” foreshadowing the mortal losses both Montagues and Capulets will suffer before the titular star-crossed lovers reunite in death.

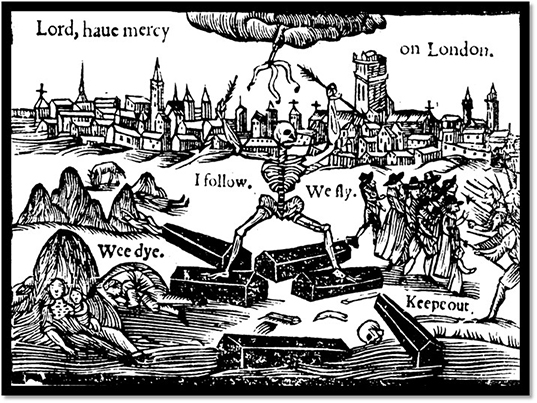

A chilling curse when the play was first published around 1596, an era when scores of Europeans and Asians were dying in waves of infectious disease. The line provides one of William Shakespeare’s few tangential references to the plague in his plays — in spite of the fact that those surges began in the mid-1300s and spanned his entire life (c. 1564-1616). Even if the recurring epidemics of the medieval era did not serve as explicit backdrops in his work — or that of most of his theatrical contemporaries — they dramatically influenced the Bard’s output.

“In some ways, he would not exist without the plague,” says FGCU Professor Rebecca Totaro, a medieval literature expert and author who teaches the course “Literature of the Plague.” “Shakespeare’s sonnets? Written in plague years. Most of his tragedies? Written when theaters were closed due to the plague. Playwrights and actors had to do something with their time. He was writing like a madman when the theaters were closed.”

An associate dean of the College of Art & Sciences, Totaro was invited to discuss that topic, as well as how today’s writers and audiences may grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic, on a podcast called “Shakespeare Unlimited” produced by the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. Her interview was recorded early in the pandemic.

Totaro has a long association with the Folger, the repository of the world’s largest collection of printed Shakespeare works, and is frequently consulted as a preeminent scholar in the literature and culture of early modern England. She has published five books on the premodern experience of plague and other historic calamities.

Ironically, Totaro was “feeling done” with plague scholarship just as opportunities for interviews and writing on the subject amped up with demand for historical perspective.

“It’s certainly the topic of the hour. The floodgates have opened,” she says. “I felt like I didn’t need to write another plague book, but there is so much to write about. There could be a hundred books. As we know from COVID-19, very unfortunately, a pandemic touches every aspect of lived experience.”

Now, as in the past, epidemics also expose weaknesses in health care, Totaro says. Other commonalities she cites: people spreading disease through travel; feeling emotions of shock, fear, sorrow and anger but also hope and courage; and pursuing positive actions, such as caregiving, connecting with others and showing charity.

“The human emotions connected to these events are the same across time and place,” she says. “It’s almost like time travel. Students reading plague literature today realize we’re not that far away from the past.”

Current events will undoubtedly cast Totaro’s plague literature class in a new light when she teaches it again this summer. The curriculum focuses on 1500 to the 1720s, when 50%-70% of victims infected by bubonic plague died within three to five days of experiencing its grisly symptoms.

After teaching the course for 20 years at FGCU, she expects that students will approach the subject with a different perspective on social behavior, mortality and loss based on what they’ve experienced living during a pandemic since early 2020. It won’t be as easy to shrug off medieval times as an ancient period of chaos, primitive apothecaries and mass death.

“Students in the class always say things like, ‘Well, back in those days, so many people were dying that they got used to it. If a family had 10 children and only three lived it wasn’t a big deal,’” Totaro says. “I say baloney! It’s always a big deal when a child dies. There’s no way you get used to it.

“There’s a lot of stuff like that I won’t need to reinforce now. The tone will not be so lighthearted, I’m sure” she says.

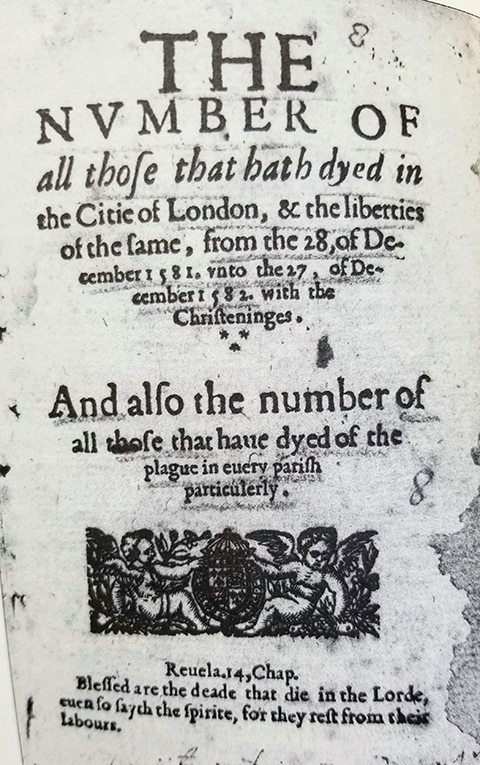

The curriculum is based on literature Totaro has been collecting and studying for a couple of decades: medieval and early modern poetry written in grief, informational pamphlets published by civic and church authorities, rare personal accounts such as “Meditations in My Confinement” by poet Thomas Clarke, and even utopian novels that imagined a better life after the plague years, which finally ebbed in the early 18th century.

Before periodically produced newspapers started to become common in the 17th century, bills of mortality were distributed that informed citizens of the plague’s death toll. Obviously not as timely as the daily COVID casualty counts we see today, but a major leap ahead in communication for the time.

“Someone on your block would get one and tell their neighbors,” Totaro says. “It was the first time that deaths were recorded and associated with a particular disease. People could find out where deaths were happening and make more informed decisions.”

In the Folger podcast, she mentions an account of a woman who died simply of fear that a stranger assaulting her on the street had exposed her to plague — a sensibility or superstition that might partly explain why Shakespeare and his peers avoided the topic like, well, like the plague. Was re-creating the horror of Black Death on a stage somehow “too real” — or “too soon” as we say now — even for an author of gore-laced fictional tragedies and history plays?

“No dramatist in the period chose to dramatize those directly affected by plague, such as victims or survivors mourning the loss of family or friends. Who would want to watch that? It’s a horrible death,” Totaro says. “In some cases, we could say the theater closings took care of that decision for playwrights. Even if they wanted to put on a plague play during plague time they couldn’t have anyway.”

Eventually, Shakespeare turned to writing romances like “The Tempest,” “Cymbeline” and “The Winter’s Tale,” stories with uplifting resurrections of characters thought dead and reunions among family, Totaro says.

In the Shakespearean era, she adds, there was no zombie apocalypse narrative — unlike today. American culture is saturated with dystopian storylines, along with instant information and social oversharing. How will these conditions shape pandemic literature when it emerges?

“One of the cool things about studying plagues or pandemics is the surprising number of stories of hope and joy and resilience,” Totaro says. “Maybe utopia is where literature needs to go. We’re really going to need that type of thinking to deal with this. The world needs to come together, communicate better across lines. We’ve all been going through the same emotional experience, no matter what country we live in. To write a utopian work that would unite people — that would be the challenge.”

- Listen to the “Shakespeare Unlimited” podcast