Just a few years ago, the senior from Immokalee, a self-described “tinkerer,” was planning a career as an auto technician – an admirable skill and a big step for the son of a migrant farm worker. This spring, Hernandez-Isidro will take his first steps toward a profession, but in a field more advanced than vehicle repair — and in a field light years away from the agricultural fields where his family has carved out their life.

As the soon-to-be recipient of a bachelor of science degree from FGCU in bioengineering, Hernandez-Isidro’s own American Dream uproots him from the most modest of beginnings in a small Southwest Florida farm town and catapults him to a new world, where he grows into a medical-technology innovator of tomorrow.

This meteoric rise is — perhaps more than anything — both a tribute and gift to his father.

“My dad has worked in the fields most of his life,” Hernandez-Isidro said. “He only got to finish second grade in Mexico. My mom always tells me I’m living his dream for him. I can’t express how much that means to me.”

His father, Genaro Hernandez, 41, brought the family from Mexico to America when Cesar was a young boy. He has made a steady-but-hardscrabble living following the tomato harvests with his wife, Lourdes Isidro, and their four children in tow. “My dad is big on family,” Hernandez-Isidro said. “He’s far from his family in Mexico, so keeping the family unit here together has always been very important to him.”

The Hernandez-Isidros, who had settled in Collier County, would migrate as a family from their home to farms in north Florida, Georgia, Tennessee and the Carolinas, the children changing schools as Genaro followed the work. “That’s something that not many migrants do,” Hernandez-Isidro said of his family traveling together. “A number of my friends and their families stayed in Immokalee while their fathers followed the crops.”

Regularly changing schools in different regions of the South during the academic year was a challenge, but the communities the Hernandez-Isidros called temporary homes “all shaped me into who I am,” Hernandez-Isidro said.

He would remain in Immokalee for his junior and senior years of high school, where he was dual enrolled at Immokalee Technical College his junior year of high school through the first semester of his senior year. He then dual enrolled at Florida Southwestern State College to finish his second semester of his senior year. In fact, Hernandez-Isidro’s participation with the technical school team’s entry in FGCU’s SunChase Solar Go-Kart Challenge was his first introduction to the university’s main campus.

Teachers working in the gifted program at Immokalee High School soon saw more in Hernandez-Isidro than a young man who could learn to rebuild engines and transmissions. “They looked at my grades and test scores and asked me why I wanted to settle for that, told me that I was capable of so much more.”

It was the type of encouragement he had never heard before. “I was always told by people in my community that I couldn’t go to college because of my immigration status, because I wasn’t born here,” Hernandez-Isidro said. “Those things hurt. The one thing I can’t control is where I was born, and that’s the biggest obstacle I have to overcome. My parents, though, always supported me, told me not to listen to the negativity. They always pushed education. They knew it was the only thing that would take us out of poverty, out of the circle of just ‘settling.’”

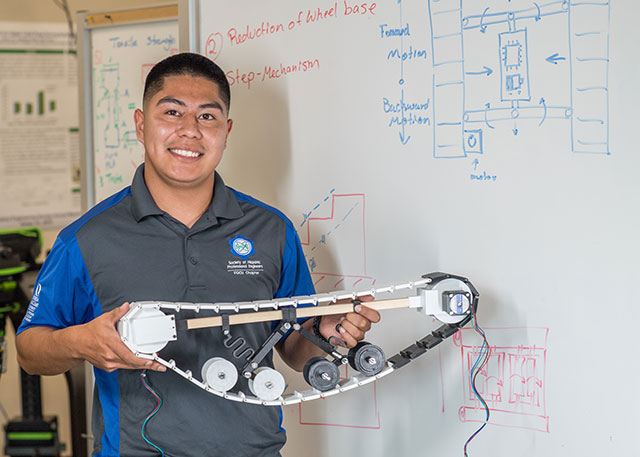

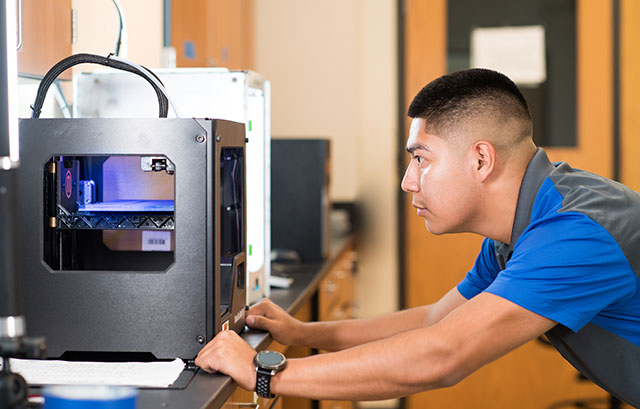

That’s how he became a first-generation student at FGCU, where he’ll leave in the spring with not only a degree but with research experience on impactful projects such as an all-terrain wheelchair. He’ll graduate with the prospect of a doctorate in engineering on the horizon, and, most importantly, the satisfaction of transformative accomplishment that can only be felt by the son of a Mexican migrant worker who is about to become a young professional who plans to make a difference in the world. His family-instilled work ethic was further fueled by mentors and benefactors.

“FGCU Foundation scholarships, community scholarships … all the local scholarships helped me get through college,” said Hernandez-Isidro, who, for example, said he got to work on the wheelchair research project thanks to a summer scholarship through the Whitaker Center for STEM Education. “I’m not eligible for any federal scholarships because of my immigration status.”

He’s still undecided whether he’ll pursue secondary education (“I’ll try to do research on prosthetic devices if I go to grad school”) or begin a professional career. “I want to go into biomechatronics if I enter the industry,” Hernandez-Isidro said, referring to the interdisciplinary science that integrates biology, mechanics and electronics. “My biggest dream is to work with exoskeletons.”

The reason he hopes to purse exoskeleton development isn’t surprising. “The fields have taken a toll on my dad’s body,” Hernandez-Isidro said quietly, then paused a few seconds to collect himself. “It saddens me a lot. My whole life, if I wanted to play basketball or catch with him, he was always too tired. He worked so hard to give us the best he could, and it was at the cost of his body. I want to build devices that help agricultural workers like him, or anyone who works at labor-intensive jobs, to help lessen the load. My ultimate dream is to build something like the ‘Iron Man’ suit that provides assistance with the workload and with rehabilitation. I think it’s very important to create devices that improve the lives of people.”

As the oldest child in his family, Hernandez-Isidro also is paving the path for his younger siblings. “My sister is a sophomore at Immokalee High School, and she wants to study in the medical field here at FGCU, and is gearing her curriculum toward that,” he said. Hernandez-Isidro also has a brother who’s a freshman at Immokalee High and another brother in elementary school.

Whether the younger Hernandez-Isidros achieve what their older brother has thus far might depend on whether they follow his relentless drive to “always be the hardest-working person in the room, and then try to outwork yourself. Remember that nobody’s entitled to anything. You may have the talent, but if you don’t put in the work, you won’t go anywhere. Block the noise, don’t listen to negativity. Stay focused on your goals. Through hard work and education, anything can be achieved.”

While Hernandez-Isidro provides the hard work in that equation, it has been FGCU that has afforded him the education. He cites professors Derek Lura and Jorge Torres of the U.A. Whitaker College of Engineering faculty — “They have given me the tools to do research, excel as a student and be a better communicator of ideas” — as two of his most influential mentors. Beyond the classroom, he cites his experiences in Housing and Residence Life as a resident assistant and desk worker with “helping me develop communication skills that will also help me in engineering.”

“This university has given me so many things … opportunities of a lifetime I never would have expected,” he said. “Here, you really are a name, not a number. My professors know who I am, not only on a student level, but on a personal level. In engineering, we build a sense of community … friendships, relationships, camaraderie, networking. Because the college is relatively small, professors have more input into what we learn, and why we are learning it. Everyone I’ve met here inspires me to continue. I wouldn’t have had the chance to do undergraduate research, be able to advocate for education, and to represent my community at any other school like I get to do at FGCU. And the best thing is, I’m able to do everything I do and be known as Cesar — not just ‘that kid.’”

So, as a young man who has accomplished about all one could possibly achieve in 21 years, given his humble start in life, what advice does Cesar Hernandez-Isidro have for others who are beginning their own journey to The American Dream from the same place he did?

“People in my situation are scared,” he said. “They feel hopeless about overcoming the obstacle of being an immigrant to get a college education. Everything I’ve done has helped me move one step closer to my dream, to grow, to learn something new. It’s not easy. But if you are up for the challenge, I believe you can do just about anything.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]ABOUT FGCU CHAMPIONS

They are the FGCU Champions — proud advocates for the university, mentors to students and alumni alike, and dedicated educators. They are tried-and-true Eagles. And they back up their loyalty to FGCU by committing their financial support as well as their passion. Follow their lead by becoming an FGCU Champion and be the difference that makes a difference. Over the next few weeks, read about other FGCU Champions at FGCU360 like Maria Roca, J. Webb Horton and Win Everham.