Amid the chaos and disruptions left behind after Hurricane Irma roared through Southwest Florida last September, FGCU’s Communities in transition initiative sprang to life.

For four years, the initiative had provided support for professors who wanted to engage in research addressing issues in the surrounding community, says Billy Gunnels, director of undergraduate scholarship. But, he says, the category 3 hurricane “brought about a large collective realization that ‘You know, we need to do something. What can we do?’” The answer was clear, he says: “The most important thing we can do as a university is use our expertise to help address the concerns, issues, problems that the community wants addressed.”

Now, Gunnels says, “We have four different teams made up of eight faculty, 26 students, working on four projects.”

Their subjects are as varied as sprawling, diverse Southwest Florida itself:

- Flood mitigation and water management in the booming village of Estero

- How past generations in remote Everglades communities have passed down knowledge needed to deal with a big storm in the low country.

- The use of modern, environmentally friendly chemistry techniques to avoid the toxic chemicals that can be unleashed in a storm.

- Offering free health screening sessions to accumulate data that could ultimately improve medical care in the low-income, agricultural community of Immokalee.

Whatever the subject, Gunnels says, students learn to solve problems faster and better in the field than in the classroom – and that’s not lost on prospective employers they may encounter.

“One of the things about the real world, for lack of a better word, is that it requires a tremendous amount of creativity,” he says.

ORAL HURRICANE HISTORIES

People in remote Everglades communities can’t count on outside help when a hurricane strikes – but they still don’t have to face the threat on their own.

They have the hard-won knowledge of hurricane survival that’s come down through the generations to the tight-knit communities of Everglades City, Chokoloskee and Copeland.

That information isn’t written down, so this year a team of students and professors from FGCU interviewed residents to learn what they have learned.

“What we were doing was collecting oral histories of hurricane experience but also of family and local culture and the experiences that surround hurricanes,” says Katherine Wahlberg, an instructor in the Department of Social Sciences. “And we then took those oral histories and we’re creating a video about the experience, a documentary.”

The students arrived prepared for their task, she says. “The first five weeks they spent doing research on the area, so when we went down there to Everglades City, Copeland, Chokoloskee, they had a good amount of knowledge. We wanted them to come into it having that kind of background.”

Then they spent eight days in June conducting interviews, winding up with 13 oral histories of 45 minutes to an hour each.

The students learned that much of the knowledge passed down is intensely practical: ways to stay afloat literally and financially in the aftermath of a storm.

“They would prioritize their boats above anything else,” student interviewer Kinsey Brown says. “A lot of the time they will take them up little rivers and small channels up in the Everglades and they will tie a rope to all four corners of the boat, securing it effectively into the mangroves.

“If you tie it correctly, the boat will rise and fall with the water,” Brown says. “So you don’t have to worry about losing your boat and also your livelihood and your home and all of your material possessions all in one fell swoop.”

Residents have also incorporated hurricanes into their lives in a broader sense, says Melissa Minds VandeBurgt, assistant librarian in charge of Archives, Special Collections, & Digital Initiatives at the FGCU Library.

“The hurricanes are interesting because they’re integrated,” she says. “They’re part of the history. They serve as these kind of touchpoints in cultural memory where people can work off of them and kind of remember their own history and their own cultural history. They serve as reference points in people’s memories.”

Everglades residents often see hurricanes almost as living creatures, VandeBurgt says. “So many people will refer to them as ‘she,’ as entities. They were beings, like they really do have this presence as more than just a weather thing that happens.”

At the same time, Brown says, residents don’t always feel the terror most people would with a hurricane bearing down on them.

“They’re very comfortable with hurricanes,” she says. “There have been a lot of them. They’ll walk outside during a hurricane without thinking twice about it.”

People in the Everglades have also developed a culture of interdependence that’s helped them deal with a hurricane even though relief efforts from outside are slow coming to the remote communities, Wahlberg says.

It’s hard for outside relief agencies “to have a broad organization that helps everybody equally,” she says. “So we’ve seen the community and how this depth of time and knowledge of hurricanes really informs how they understand hurricanes and how they experience them and then the preparation, the decisions they make, and how they help each other.”

For example, Brown says, “We heard a story about a man who got in his truck when the floodwater hadn’t come in yet, and drove off to go check up on people. He was driving around in the storm in his truck, checking on people.”

But when Irma’s floodwaters arrived faster than expected, the man was stranded on the side of the road in the truck.

“So he gets a call from his family who’s riding it out,” Brown says. “And everybody who was safe inside, they got on a boat and they went out after him, the second he said he was out in the storm. And he told them not to come after him and they still went out and got him and they made sure he was OK.”

TRANSFORMING GOLDENROD

Two FGCU chemistry professors hope to achieve what legendary inventor and Fort Myers winter resident Thomas Edison could not: a safe, efficient way of producing rubber from goldenrod.

Their inspiration: the massive explosions and toxic waste spills in a chemical plant near Houston, Texas, after Hurricane Harvey struck in August 2017, two weeks before Irma arrived in Southwest Florida.

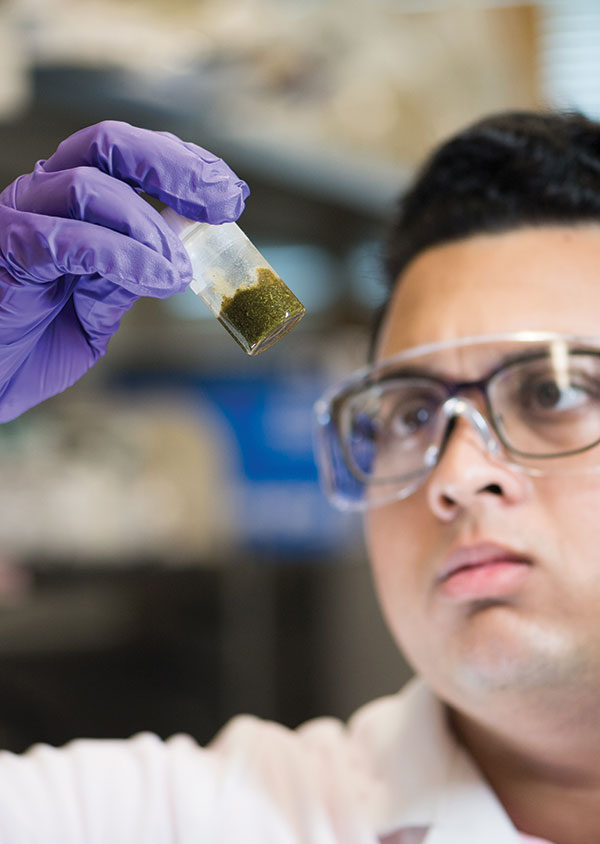

The team’s immediate goal is to use an environmentally friendly class of chemicals called ionic liquids to extract isoprene – the main component of rubber – from goldenrod.

That could be useful commercially, but it’s just a starting point, says Associate Professor Arsalan Mirjafari, who with Assistant Professor Gregory McManus is conducting the project.

“Isoprene is step one,” Mirjafari says, but ultimately the ionic liquids could be used to supplant a host of dangerous chemicals used in industrial processes.

The ones that exploded in Texas were organic solvents that need to be kept at extremely low temperatures to stay stable, he says.

They blew up because loss of power caused refrigeration units to fail after the storm, Mirjafari says. “The temperature went up and they exploded.”

Edison also had to use organic solvents in his own efforts because ionic liquids hadn’t yet been developed.

“It was a nasty process,” Mirjafari says. “He couldn’t do it. We’re trying to make the process greener and more efficient.”

Edison crossbred a strain of goldenrod at the Edison Winter Estate that grew 12 feet high and had a high yield of isoprene. Mike Cosden, executive vice president at the Edison & Ford Winter Estates, says they still grow that strain on the estates’ grounds and donated some to the FGCU team for its experiments.

Edison died in 1931 without succeeding in commercial production of rubber. The project continued after his death, but was abandoned because synthetic rubber was easier and cheaper to produce, Cosden says.

Taha Hmissa, one of the students doing the lab work on the project, says that if they’re successful at extracting isoprene, other uses might be possible.

For example, he says, phosphate mines are a major industry in the Miami area. “There are lots of phosphate-treating facilities there that use toxic chemicals because of all the mining that goes on there.”

Mirjafari says the project is good science but also a good way to educate the students who are involved. “When you train students to have a hands-on experience, they will learn better than going to the class and just talk,” he says. “You have to engage the students, they have to learn how the science works and they have to get excited.”

Hmissa says working on the project has had just that effect on him.

“That’s one thing I really do like about this project,” he says. “Dr. McManus and Dr. Mirjafari force you to go out there, they force you to e-mail people, force you to contact people. They say, ‘Hey, you’re not going to do this alone. Contact the Edison and Ford Winter Estates, contact these different companies, try to research what happened in Houston.’ They really want you to be able to network with people, make connections, collaborate, gain these social skills, because this is a project that will show you decades from now how to work as a scientist, and that’s what we all want to do, all of us that are in the lab.”

FLOODING

A team of FGCU researchers is unleashing a flood of information in response to the literal flooding caused in Estero by Hurricane Irma in September 2017.

Don Duke, professor of environmental studies, and Serge Thomas, assistant professor of environmental studies, are both presenting reports to the Village of Estero on their findings, compiled with the help of a group of students.

With the massive outbreak of blue-green algae in local waters this summer, the reports are coming at a time when people are keenly aware that water resources are important, Duke says.

“I’ve been working on water resources the whole 10 years I’ve been with FGCU,” he says.” And Florida’s water resources have been growing in concern and in public awareness pretty much that whole time but it’s really at a peak right now.”

Duke says his report to the village will cover topics including an inventory of the stormwater ponds that exist in gated communities and a study on how land uses have changed.

Thomas will issue a report on flow studies of ponds on and near the FGCU campus and how that relates to ponds in Estero.

Yiliannis Rodriguez, an environmental studies major, says her group measured the levels of the FGCU ponds and determined how much they rose or fell after a specific amount of rain.

“By doing that we were able to create a formula that we could use to see how much the ponds rise,” after a specific amount of rain, she says.

The formula includes the amount of surface on campus that’s permeable and impermeable to water, and also the total surface area of the ponds, Rodriguez says.

Using the formula, “We were able to use campus as a residential community to compare to the communities in the Village of Estero,” she says.

Now, she says, the Estero communities will be able to estimate how high their ponds will rise after a storm that drops a specific amount of rain. “By knowing that, they can try to figure out if they need to work on their drainage systems or do something to fix their ponds to hold more water.”

As students go out into the community to solve real-world problems, Duke says, word gets around that “FGCU is a major player in addressing those issues and producing students who are well equipped to go into that in their careers.”

Two of the students working with him on the project got internships with government agencies and one of those two got a job with a consulting firm, Duke says.

Rodriguez says she hopes to go into the water management field when she graduates and she’s already starting to understand the benefits of getting out into the community.

“I knew it would give me experience for what I wanted to do, and it’s really helped me make connections and meet new people and learn more about water management and flooding,” she says. “So yes, it’s helped me a ton.”

IMMOKALEE HEALTH CHECK

Some FGCU students headed for Immokalee this summer to help residents deal with the damage to housing from Hurricane Irma – and also combat lingering health problems caused by the storm. “The whole idea is to find out in what way Hurricane Irma has impacted the housing situation and how the housing situation has impacted their health,” says Payal Kahar, an assistant professor in the Department of Health Sciences.

Also, she says, “There are other initiatives in this project such as just preparing them for future events – if such a hurricane took place this hurricane season, in what ways are they better equipped and prepared to mitigate the effects the hurricane brought.”

Kahar and Lirio Negroni, an associate professor in the Department of Social Work, are leading the project.

This summer’s work built on a smaller data-gathering project by FGCU students and staff after Irma came through in September.

In August and September, students conducted six free weekend health screening events in locations around Immokalee.

“In the findings of the first study, which was exploring the health needs, we learned about health conditions that may need to be addressed in Immokalee,” Negroni says. “We began to talk to agencies and health centers to learn more about the health situation.”

The screenings came about because she and Kahar “felt that we not only should be going to Immokalee to gather data. We want to do something to contribute in some way,” Negroni says.

The screenings are “a way for residents in Immokalee to find out about conditions they were not previously aware of, and what it is they could do to prevent further risk in the future,” Kahar says.

Screenings are “not directly related to hurricane impacts, but then again looking at the health effects natural disasters have. They could be acute exaggerations of chronic conditions,” she says. “For example, asthma could worsen following a hurricane. There’s moisture in the house, the walls fall in.”

With all those components, the summer’s work is a big job, Negroni says at an orientation meeting for students before they head to Immokalee.

“There’s a little bit of anxiety about how we’re going to do all this as a group and how the community’s going to respond,” Negroni notes at the session. “It’s worrisome, it’s anxiety-provoking and it’s exciting.”

Logistical details aren’t all the students have to concern themselves with, she said – a major issue has been building trust in the Latino community, mainly people from Mexico and Central America.

Seemingly minor details can show that the health screenings are on the level, Negroni tells students. For example, they’ll all wear T-shirts emblazoned with an FGCU logo and “Immokalee Latino Health Project”. A cheer went up when student Rachel Walter announced that “I just got a text from the vendor that the T-shirts are done.”

When the summer’s work in Immokalee is completed, the task of analyzing a mountain of data from surveys and focus groups will just be starting, Negroni says.

“We’ll be here until December, working,” she says, adding that she hopes FGCU will continue the initiative next year and in years to come.

“The whole idea is that once we gather the data, we could pass it on to other organizations in the community so that they could direct their initiatives toward addressing the issues that are more prevalent” throughout the study’s results, Negroni says.